|

Oregon Pacific Railroad Corvallis & Eastern Railroad Willamette Valley & Coast Railroad |

|

|

|

|

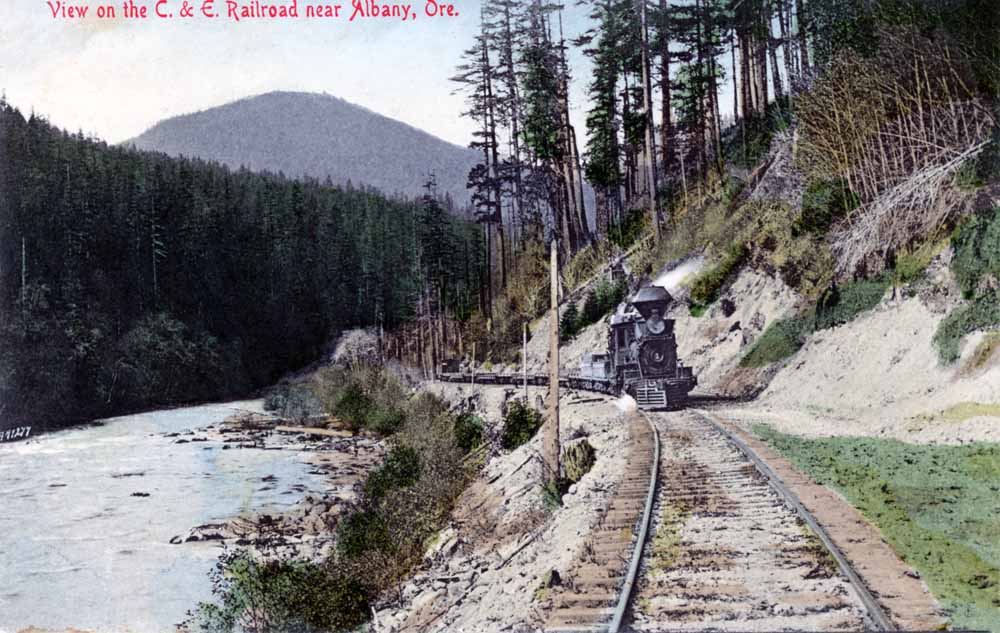

A vintage colorized postcard view of a Corvallis & Eastern freight in the Santiam River canyon. |

|

|

Special Note: This page is about a historical Oregon Pacific Railroad. It should NOT be confused with the modern Oregon Pacific Railroad, a shortline operating several pieces of disconnected track in northwestern Oregon. The current Oregon Pacific maintains a website at http://www.oregonpacificrr.com/ |

|

|

History Corvallis had been the most important town in Oregon's Willamette Valley for many years. However, in the early 1870s that picture began to change. The city lost the state capitol when it moved to Salem, and the central lines of commerce started bypassing the community in favor of Eugene. The town knew it needed a railroad to ensure a lasting place on the map, but the best hope for one stalled out at Hillsboro, far to the north. Colonel T. Egenton Hogg arrived in town in 1871 with big plans for a railroad that would place Corvallis not only on the map, but also on the line of a major transcontinental railroad. In October 1872 Hogg organized the Corvallis and Yaquina Bay Railroad, which did nothing of any lasting importance. On 6 July 1874 Hogg organized a second railroad, the Willamette Valley & Coast. The WV&C finally got things going, with ground broken at Corvallis on 17 May 1877. Hogg planned to run the railroad from Yaquina Bay, on the coast west of Toledo, eastward through Oregon and into Idaho where he planned a connection either with the Oregon Short Line in the neighborhood of the Idaho border or with a possible westward extension of the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad. While Hogg focused most of his initial efforts on the western end of his proposed railroad, he did not neglect the eastern parts of the state. Hogg made sure the railroad's planned route ran through Prineville, the most important community in the region, and he spent a lot of time traveling through the rest of the area gathering support for his plans. The feedback Hogg received prompted him to add two long branches to the system, one that would have started around the confluence of the Crooked and Deschutes River and run northeast to Umatilla, while the second would have extended from around the modern site of Burns south to Winnemucca, Nevada. |

|

|

|

|

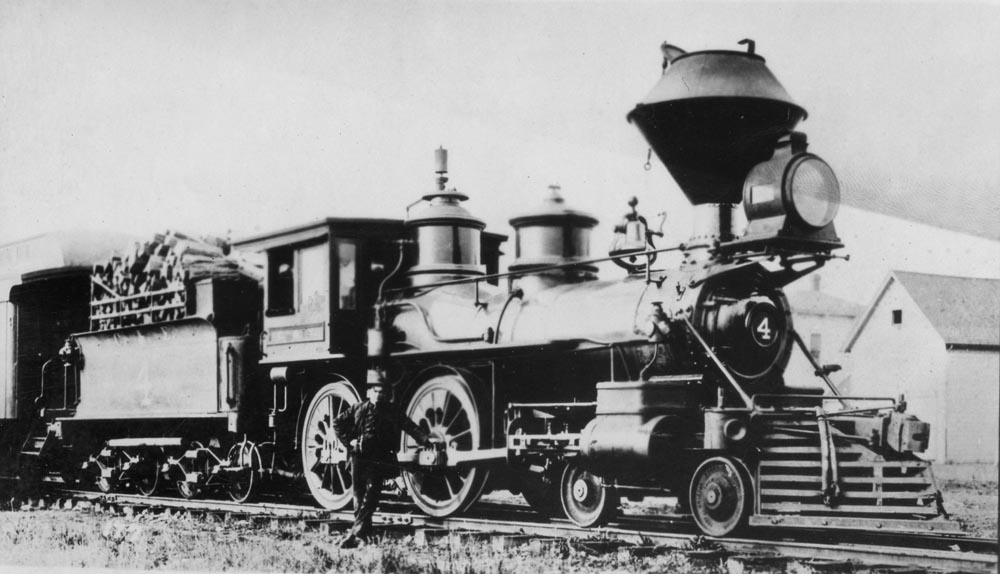

Corvallis & Eastern #4 at Corvallis in 1906. |

|

|

|

Despite his constant efforts, Hogg was having trouble raising funds, and as such the WV&C only

managed to build ten miles of track east from Yaquina over its first year before construction stopped.

Hogg's slow progress left the door open for competition, and in January 1880 the Western Oregon Railroad

put Corvallis on the railroad map when it completed a line into the city from the north. Transportation

magnate Henry Villard controlled the Western Oregon, and he recognized the WV&C as a potential threat

to his empire, which at the time included the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company. If completed, Hogg's

railroad would provide a substantially shorter and flatter route east than his combined railroads, which would

have put his operations as a serious competative disadvantage. Hogg's prospects did not substantially improve through 1880, and in September of that year he incorporated a third railroad, the Oregon Pacific, which took over the WV&C. The new company improved the fundraising picture, and by the fall of 1881 Hogg had enough financing in place to get construction moving again. However, Villard refused to handle any Oregon Pacific traffic over the Western Oregon Railroad, and with land access cut off Hogg had to use his port facilities at Yaquina Bay to bring all needed supplies and materials in by boat. On 31 December 1884 construction crews spiked down the last rails completing the Corvallis- Yaquina City line. With the route over the coast range finally completed Hogg then turned his attention eastward, with West Albany reached in September 1886. The company then built an impressive bridge across the Willamette River, and the first Oregon Pacific trains rolled into Albany on 6 January 1887. Oregon Pacific construction turned to the northeast as they left Albany behind, with Shelburn reached by the end of 1887. After passing through Shelburn the construction crews started blasting their way up the Santiam River Canyon. Unfortunately, Hogg's construction budget ran out for the final time as the railhead reached Idanha, fifteen miles short of the top of Santiam Pass, which Hogg intended to use to get his railroad through the Cascades. At least some grade extended farther up the canyon above Idanha, and advanced grading parties had built several stretches of disconnected grade in the pass itself and then partway down the east slope. Hogg had his construction crews haul a boxcar and enough rails to lay a couple hundred feet of track up to the top of Santiam Pass, where they built a short stretch of railroad on which they reportedly pulled the boxcar back and forth a few times with a mule, this done to hold the pass for the railroad. Hogg then sent the construction crews 300 miles farther east, where they built a dozen miles of grade in the Malheur River Canyon to hold that vital passage for his railroad as well. |

|

|

|

|

The completed Oregon Pacific grade at the top of Santiam Pass. U.S. Forest Service photograph. |

|

|

|

However, it was not to be. Additional money did not appear, and revenues were not enough to pay the bills

on the completed railroad. The Oregon Pacific declared bankruptcy in October 1890, with Hogg appointed

receiver. By this point many of the bondholders blamed Hogg for the failing financial state of the

company, and indeed several million dollars of money loaned or advanced to the railroad since its beginning

could not be found or accounted for in the books. The bondholders finally got Hogg removed in 1893. In

1897 lumbermen A.B. Hammond and E.L. Bonner purchased the railroad out of bankruptcy for $100,000, a fraction

of the company's $375,000 estimated scrap value. Hammond had a large sawmill at Mill City and a logging

railroad network out of Detroit, both on the railroad's line up the Santiam River, and the new owners

incorporated the Corvallis & Eastern Railroad to take over the property. The C&E operated 143 miles

of railroad with 16 locomotives, 258 boxcars, and several miscellaneous passenger coaches. The company also

had five ocean going steamships that connected the railroad with ports up and down the west coast. Thus the first dream of a transcontinental railroad through Central Oregon ended. The citizens of Oregon's desert regions had watched the advancing Oregon Pacific with growing excitement, only to have those hopes dashed with Hogg's failure. However, ruumors that the Corvallis & Eastern would one day continue work on the eastward extension of the railroad lasted for another decade, only to be finally ended when E.H. Harriman, who at the time controlled both the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific railroads, purchased the company in 1907, primarily to make sure that the Hill family and their competing Great Northern Railroad did not get to it first. The Corvallis & Eastern remained independent until 1 July 1915 when the Southern Pacific officially purchased the company. Southern Pacific turned the old Corvallis & Eastern into a branchline. The center portion of the line, from Albany to Shelburn, disappeared in 1930. The next cutback to the original Oregon Pacific came in 1937 when the westernmost part of the line, from Toldedo to Yaquina Bay, was abandoned. Idanha continued to see trains until 1950 when the Big Cliff and Detroit dams forced abandonment of the upper part of this line. The Army Corps of Engineers planned to re-route the branch around the reservoirs, but Southern Pacific decided against that. Further cutbacks through the 1970s and early 1980s saw the end of track retreat downstream, with some sawmill complexes just west of Mill City finally established as the end of track. Southern Pacific continued to operate the two remaining pieces of Oregon Pacific trackage until 22 February 1993, when they leased the Albany-Toledo trackage to the Willamette & Pacific Railroad, a new regional railroad. On the same day they leased the Shelburn-Mill City trackage to another new shortline, the Willamette Valley. Corporate reorganizations since then have seen the Willamette & Pacific turn into the Portland & Western and the Willamette Valley convey the Mill City line to the Albany & Eastern. Together these two shortlines continue to operate the last remnants of the old Oregon Pacific. As for the boxcar hauled to the top of Santiam Pass, it reportedly remained there as an idle curiosity until World War II related scrap drives claimed both it and the short stretch of track upon which it sat. |

|

|

|

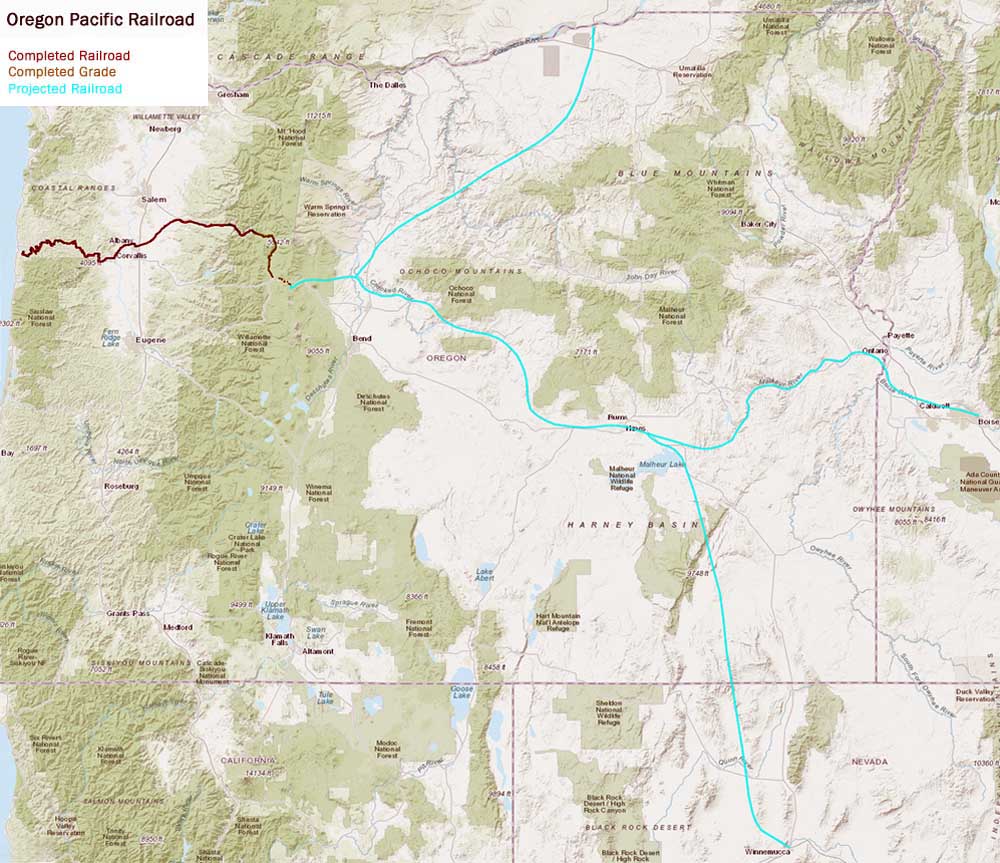

Map

The projected route of the Oregon Pacific through eastern Oregon, including the

two contemplated branches. |

|

|

|

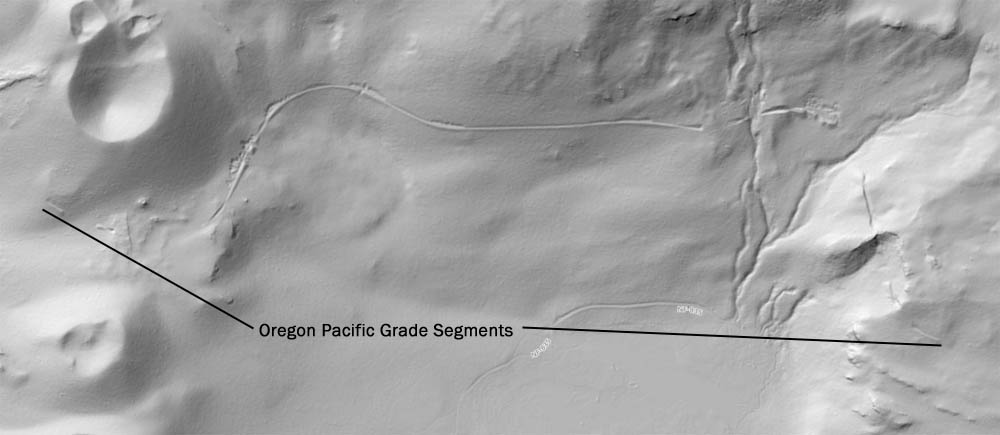

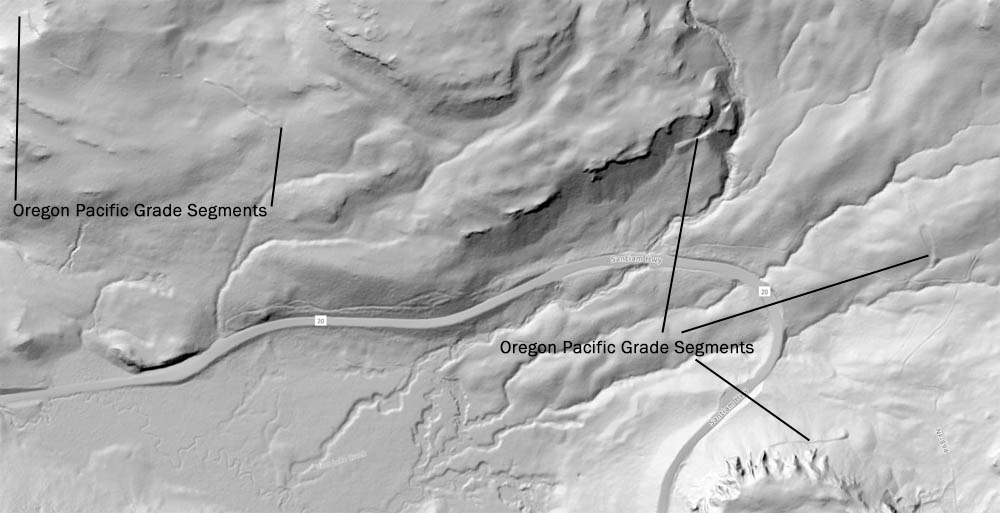

Lidar Imagery of the Santiam Pass Grades

The Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries (DOGAMI) and Oregon Lidar Consortium have been gradually building a Lidar map of most of Oregon, which results in highly detailed

terrain maps that are especially useful in identifying old railroad grades. At least some references indicate that the Oregon Pacific completed its grade from Idanha through

Santiam Pass and then a short distance down the east slope, which this site had dutifully reported for a good number of years, but the Lidar imagery disproved that notion

once it was completed. Any grade the Oregon Pacific built east of Idanha is almost certainly underneath today's Highway 22. The grade cannot be definitively located until it

appears on the hillside not far north and east of today's Santiam Junction, where Highways 20 and 22 split off the west side of the pass, and the imagery clearly shows numerous

segments of partially completed grade through the pass. The snips below are from DOGAMI's Lidar viewer, which can be accessed

here. |

|

|

The western most section of Oregon Pacific grade segments. Santiam Junction is not far off the lower left corner of this map. The middle portion is the longest

stretch of completed grade.

|

|

|

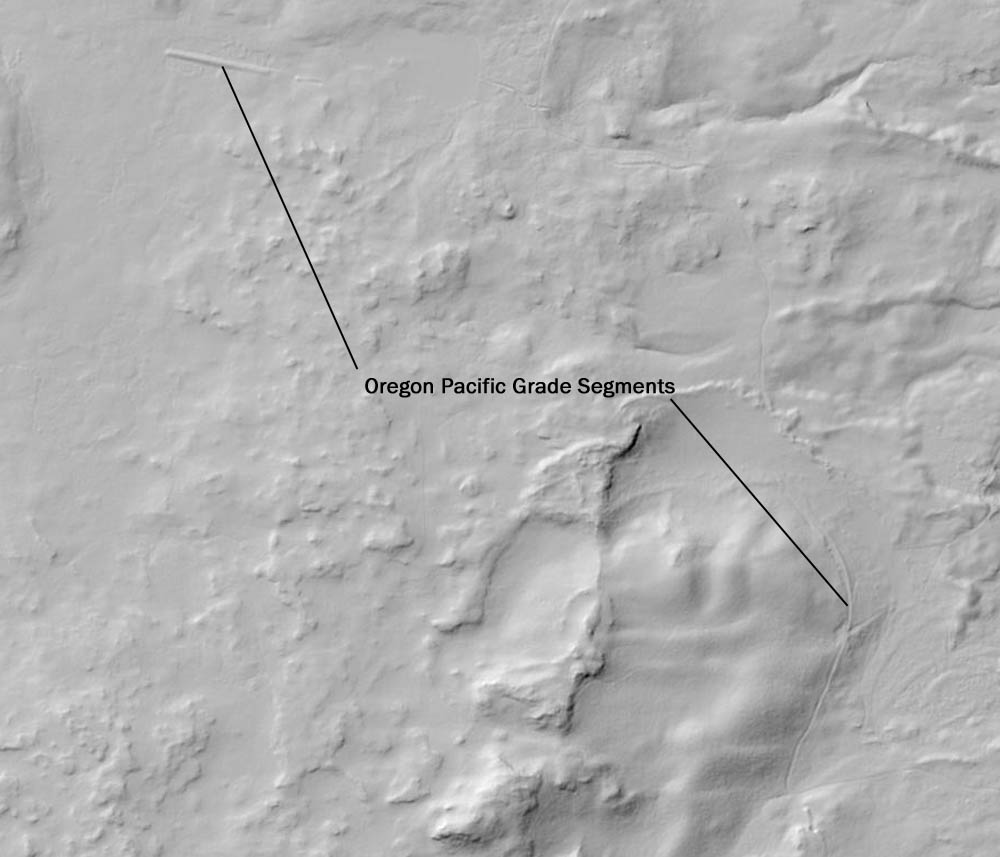

The grade segments at the upper left corner of this image are the same as the lower right corner of the image above. The railroad in this stretch completed several parts of grade, the

two sections of very preliminary cut and fill work in the drainage above Hogg Rock, and then a short section of relatively complete grade along the north side of Hogg Rock.

|

|

|

This image shows the mostly completed grade wrapping around the west and south sides of Hogg Rock. Highway 20 construction has eliminated some of the railroad grade around the face of the

rock, but this stretch also contains one of the more fascinating remnants of the railroad that never was, a fairly large rock retaining wall. The grade mostly ends just southeast of Hogg Rock, at the top of

Santiam Pass, and then picks up again a good distance to the southeast.

|

|

|

The easternmost stretches of identifiable Oregon Pacific grade. The section in the upper left corner is the same as the lower right part of the above image.

|

|

|

|

Santiam Pass Today

Below are four photographs of the Oregon Pacific grade at the top of Santiam Pass

as they appear today. All four photos taken in August 2004 by Jeff Moore. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Steve Moore shot this photo of the Oregon Pacific grade above Highway 20 on the face of Hogg Rock in April 2022. The large rock retaining

wall is visible towards the left side of the image.

|

|

|

|

References Books "Backwoods Railroads, Branchlines and Shortlines of Western Oregon" by D.C. Jesse Burkhardt, Washington State University Press, 1994. "The Southern Pacific in Oregon" by Ed Austin and Tom Dill, Pacific Fast Mail, 1987. "Railroads Down the Valleys", by Randall V. Mills, Pacific Books, 1950. "Rails to the Ochoco Country, The City of Prineville Railway" by John F. Due and Frances Juris, Golden West Books, 1968. |

|

|

|

More on the Web Brian McCamish has much of the completed Oregon Pacific covered on his website on the following pages: Southern Pacific Yaquina Branch Portland & Western Albany & Eastern Be sure to check out the various links he has on these pages as well. |

|

|